Australia’s Contribution to WWI

War is announced

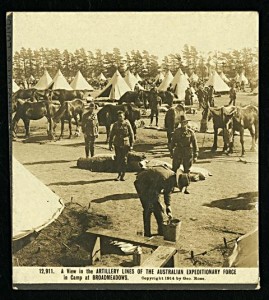

Horse lines at Broadmeadows Military Camp. Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria.

The coming of war, declared on 4 August 1914, caught most Australians by surprise even though there had been a climate for war for many years. An expectation had arisen of a clash between Europe’s two major trading nations, Britain and Germany.

Australia was in the middle of an election campaign when war came. Both leaders, Joseph Cook, Prime Minister, and Andrew Fisher, leader of the Labor Party, promised Australian support to Britain.

Labor won the Federal Election and became an enthusiastic ‘win-the-war’ party in government. Supporting the initial pledge of 20,000 men, the new Government watched an extraordinary rush to enlist all around the country and soon promised an increase in the expeditionary force to take the total to 50,000 men.

Find out more about Australia’s Prime Ministers

First recruits

Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria.

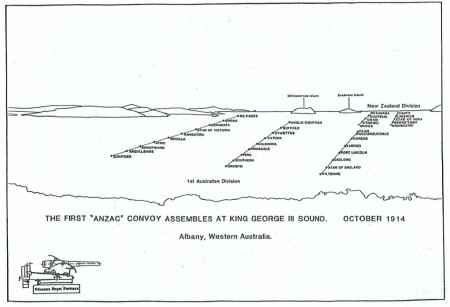

The recruits were wildly popular in their various marches and parades in each of the capital cities and as the first troopships departed Australian shores in late October 1914 there were large crowds on hand to say farewell.

Instead of going to Britain, which everyone had expected, the troops were diverted to Egypt, largely because it was feared the Australians would not withstand the terrible English winter in makeshift camps on Salisbury Plain. It was tough in Egypt too, with basic facilities, and not much in the way of training beyond marching up and down the sand dunes and deserts.

Although some Australians misbehaved and were sent home, the vast majority accepted that a soldier’s life can be pretty tough. There were rumours throughout the camp about where they would fight and in April it was confirmed that the Australians, alongside their New Zealand comrades, would attempt an invasion of Turkey to open the Black Sea to the Allies as a supply route for beleaguered Russia.

Landing at Anzac

Australian and New Zealand soldiers, Gallipoli Peninsula, 1915.

Sending troops to land from the sea on hostile territory against a well-prepared enemy has rarely been attempted in all the annals of military history. That the Anzacs (as they soon began to be called) gained a toehold at all on the Gallipoli Peninsula was considered remarkable and that they repelled all Turkish attempts to drive them back into the sea was an indication of their bravery and determination.

The Landing at Gallipoli captured the imagination of the Australian public as no other event in Australian history has ever done. The news provoked a rush of Australian recruits to the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and eventually 320,000 Australians would serve overseas in the war – an extraordinary contribution from a nation of just over four million people.

Enthusiasm for the war continued even though the Anzacs were evacuated from Gallipoli in December 1915, leaving more than 8,000 Australians in lonely graves dotted around Gallipoli.

The Western Front

After re-training and refreshment in Egypt, and with the expansion of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) to accommodate the huge number of new recruits, the Australians set off for France and the Western Front. Arriving in late May they received an enthusiastic reception from the French people, who were amazed men would travel from the ends of the earth to help France in its greatest crisis.

1916 and 1917 were years of unrelenting and horrible fighting for the Australians and they suffered huge losses which dwarfed the casualties experienced at Gallipoli. At Fromelles on 19-20 July 1916, the Australians suffered 5,500 casualties overnight on what was described as the worst day ever in Australian history. In seven weeks fighting at Pozieres and Mouquet Farm from 23 July 1916 onwards, the Australians suffered 21,000 casualties. In 1917 the deaths continued at places such as Bullecourt and Passchendaele in Belgium.

- http://www.ww1westernfront.gov.au

- http://www.army.gov.au/Our-history/History-in-Focus/WWI-The-Western-Front

- http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/australian-story/australians-on-the-western-front

- http://www.awm.gov.au/blog/2012/04/23/in-their-own-words-anzacs-of-the-western-front/

Conscription

Henley-on-Yarra just before the outbreak of war.

The numbers of recruits dwindled in Australia from early 1917 onwards, possibly because there were few men with the capacity to enlist. The work of the nation, in its factories, offices, schools and shops, and on its farms, had to be continued somehow. Yet war patriots began to think that every man in the right age group should be at the war. They demanded that the government introduce conscription. Two referenda were held in Australia in October 1916 and December 1917 to see if the people would support conscription as a method of reinforcing the AIF. The campaigns caused enormous division in the community and both were lost by very narrow margins.

- http://www.naa.gov.au/collection/fact-sheets/fs161.aspx

- http://billyhughes.moadoph.gov.au/conscription/

Victory

By 1918 the AIF was at the height of its fighting powers: experienced, grimly determined, and well led by its own Australian commanders, at last, to the great satisfaction of all Australian soldiers. (Victorian John Monash became commander of the Australian Corps in June 1918). Though savagely reduced in numbers, the AIF battalions won some remarkable victories in 1918, at Villers-Bretonneux, in the Battle of Amiens, at Hamel, Mont St Quentin and Peronne. Exhausted, the Australians were withdrawn from the line in October, after months of continuous fighting, and the war ended on

11 November 1918 when the Germans submitted to the signing of an Armistice.

The war had cost Australians dearly. It had damaged political and social harmony at home because of the bitterness of the conscription campaigns, and introduced deep religious and social divisions. 60,000 Australians had been killed in the war, many of them because of the might of the artillery, lay buried, in unknown graves. As many as 150,000 men returned home badly wounded in mind or body.