Prominent Victorians

Around 112,000 Victorians enlisted in the First World War – this number would exceed the total seating capacity of the Melbourne Cricket Ground for the Boxing Day Ashes Test.

Among the brave men and women who served in the First World War were four great Victorians.

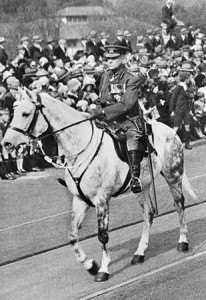

General Sir John Monash

John Monash

When John Monash died at home in Toorak on 8 October 1931 he was just 66 years of age. More than 300,000 people lined the streets of Melbourne to witness the passing of his funeral cortege and to farewell one of the greatest known Victorians.

Monash was given command of the 4th Infantry Brigade when it was formed in September 1914. The Brigade formed up at Broadmeadows and Monash proved himself an inspired and excellent trainer of men. Critics were harsh about his performance at Gallipoli but Monash learned his lessons very well. His growth and development as a strategist, thinker and leader is the most impressive aspect of his years at war.

It was his privilege and good fortune to be given command of the newly formed Australian Corps in June 1918, when for the first time all the Australian Divisions came together to form a national unit. Monash took over the Corps just when the Australian troops had reached their peak of efficiency and experience.

Monash firmly believed that his Australian troops would fight best if they knew the outline of the battle and what was required of each individual unit. He had large terrain maps constructed on the ground so that men could see every feature of the land across which they would fight.

He insisted that the troops train with the tanks that would support them until, for the first time, both infantry and tanks had great confidence in each other. He called in aircraft to assess the progress of the battle. But he also used aircraft to resupply the troops with ammunition from the air, solving one of the great hazards of fighting on the Western Front – how to keep ammunition up to the troops in battle.

Monash developed a detailed timeframe for the battle of Hamel, telling the troops that their battle would take just ninety minutes before they triumphed over the Germans. In fact the battle took ninety-three minutes before victory was secured.

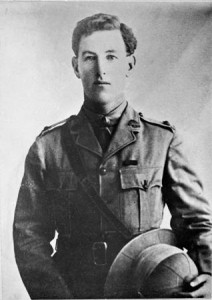

Captain Albert Jacka VC MC and Bar

Albert Jacka

‘Shy’ is the word that most have used to describe Bert Jacka, whose remarkable actions earned him Australia’s first Victoria Cross.

Born at Layard near Winchelsea in the south-west of Victoria in 1893 and living later at Wedderburn north-west of Bendigo, Bert was the fourth of seven children, four boys and three girls. Two of his brothers, Sydney and William, also served in the AIF.

Bert was in the Victorian 14th Battalion. On 20 May at about 3.30am the Turks charged Courtney’s Post. A party of them, throwing bombs as they came, jumped into a section of the trench that Bert was defending. Bert was standing in the fire-step cut into the front of the trench and was not wounded and stood at his post firing into the back wall of the trench to stop the Turks from coming on.

But it was disastrous that the enemy was now in possession of a portion of the Australian line. Fifteen minutes passed, during which time Bert Jacka alone held up the Turkish advance before he jumped out into no man’s land and, from there, back into the trench the Turks now occupied.

Bert shot five Turks and bayoneted two; another two were shot as they tried to return to their own lines. The remainder became prisoners. He then waited for the dawn, holding the trench line entirely on his own.

This was one of the most remarkable actions of the entire campaign at Anzac and for this action Bert received the Victoria Cross, the first to be awarded to an Australian in the war.

In France he was equally as gallant and some say he might have been awarded the Victoria Cross twice more. He came out of the war as Captain Albert Jacka, V.C., M.C. and Bar. He died in 1932, 39 years of age.

Brigadier General Harold Edward ‘Pompey’

Harold Edward (‘Pompey’) Elliott

Harold Edward Elliott, known to all, to his regret, as ‘Pompey’, was born at West Charlton in central Victoria, in 1878, and he simply loved soldiering. He had fought in South Africa, continued in the militia after that war, and in August 1914 he was back in the thick of it, first appointed to command Victoria’s 7th Battalion.

Told that his 15th Brigade would be one of the three Australian Brigades to attack at Fromelles, Pompey was appalled.

First the attack would commence in broad daylight. Secondly, the attackers would be pushing up into the higher ground, running directly into massed German machine-guns, able to pour lead down onto them before they were anywhere near the enemy’s trenches. Thirdly, the Germans were very well dug in indeed, and would be sheltering in their concrete bunkers, to re-emerge as the infantry came through, free to employ their massive machine-gun superiority. It was madness, Pompey raged; suicidal. But the attack went ahead.

Fromelles represented a sickening loss to the people of Victoria. The 57th Battalion came off relatively lightly. The 58th lost one third of its strength at Fromelles, the 59th suffered heavy losses and with 757 casualties the 60th Battalion was virtually wiped out. Pompey Elliott stood in the frontline shaking the hand of each of the returning survivors, tears streaming down his cheeks. Charles Bean, Australia’s official war correspondent, said of him that he looked like a man who had lost his wife, so great was his affection for his men.

The Australians suffered 5,533 casualties in total overnight at Fromelles. Pompey Elliott took his own life in 1931.

Brigadier General C B B White

Cyril Brudenell White

Born at St Arnaud in central Victoria in 1876, White worked as a banker before becoming a professional soldier, first in the Queensland colonial forces and then with the Commonwealth forces after Federation. White was appointed chief of staff to General Bridges, the commander of the Australian contingent at the outbreak of war.

After General Bridges’s death at Anzac, White began his long association with the British commander of the Australian forces, General William Birdwood. White was largely responsible for the plans for the evacuation of Gallipoli, the most successful operation of the campaign.

In France, White was crucial to the operation and success of the Australian forces. While Birdwood gave more attention to individual commanders and their soldiers, delighting in ‘meeting and greeting’, White developed the administrative efficiency of the corps. White was responsible for all the behind-the-scenes work and only a few knew of his vital contribution.

White continued to serve Australia after the war although he was happiest on his grazing property near Buangor in Victoria’s western district. Recalled to the Army as Chief of the General Staff in 1940, he was killed in the Canberra air disaster in August of that year. He left a legacy of devotion to duty and to the Army he had done so much to create.