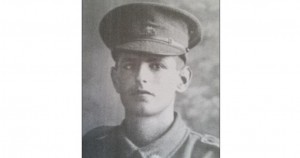

WWI Stories – Alfred Bayley

Ballarat

Valda Cuming shares the story of her father, Alfred Bayley, who was on the “Southland” when it was torpedoed by a submarine.

Alfred Bayley was born in Ballarat in 1895. In 1915, aged 17, he volunteered for the army and became a machine gunner in the 21st Battalion. He fought at Gallipoli and later in France (after surviving 36 hours on a floating spar from the torpedoed hospital ship Southland.) In France he was gassed and wounded but survived and was finally discharged on 24 March 1919.

My father survived the war but was somewhat damaged by shell shock and his lungs were affected by mustard gas. He became a dentist when he returned to Melbourne, served as a Captain in the Army Dental Corps (Melbourne based) during World War 2, and immediately post war, passed in doctorate of dentistry at Toronto University, Canada.

My father survived the war but was somewhat damaged by shell shock and his lungs were affected by mustard gas. He became a dentist when he returned to Melbourne, served as a Captain in the Army Dental Corps (Melbourne based) during World War 2, and immediately post war, passed in doctorate of dentistry at Toronto University, Canada.

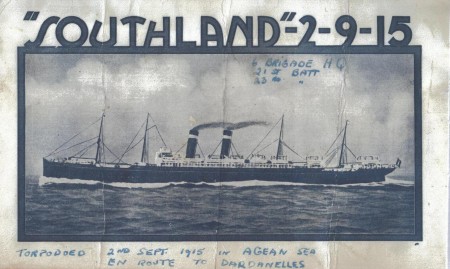

Looking through his damaged scrap book I found this photo of the ill-fated Southland with his added writing on it, and thought that this may be of interest to you. Every year, until he grew old and his mates faded away, dad celebrated the sinking of the Southland at the RSL Club, St. Georges Rd, Elsternwick, and he always returned home from this in a very happy and mellow state!

He lived a fulfilled and happy life with his wife Ena and his three daughters, of which I was the eldest. He died at seventy-five in 1970.

The following excerpt has been taken from father’s personal diary – an incredible account of the Southland disaster.

“The moment I found my bunk on the Southland I had a premonition we would be submarined. The uncanny feeling did not leave me. Each day we did our various duties, falling in …when the whistle blew …at our lifeboat stations. We were always ready for an emergency.

Sure enough, when we were about forty miles from Lemnos, just at the completion of a church parade; for it was Sunday, and we were gazing out to sea, when suddenly we heard a terrific bang on the side of the ship; another one was seen, but as were zig-zagging, it passed astern. A sub from a Turkish submarine . The alarm went so we hurried down for our life belts. Only a few had them on, probably due to the church service. However, though in haste, everything was orderly and in no time we were at our stations in the different boat decks allotted us . There were a couple of revolver shots . I heard later that the Captain fired at two of the seamen who did not obey and man the boats .

The ship started to list and took in water. The Captain gave the order, every man for himself. After several boats were lowered in my station, I , amongst fifty others, got into the boat; but unfortunately, the seaman let the ropes go with the result [that] we were precipitated into the sea from the upper boat deck down. The boat came on top of me pinning me underneath. Having a lifebelt on, I rose in the upturned boat and clung to one of the seats under water. I was under water for a time, and short of breath. Eventually I found my way and clung to the ropes and pulled myself on top. My past, Mother and Christ ran through my mind and thought this was my last – all came in a flash . I could see hundreds’ of others clinging on to anything as the load was thrown overboard to lighten the boats. I was drifting away from the ship – I thought I would get sucked in. Now this boat had water tight compartments and stayed with only a dip for a time. Such being the case volunteers were called to work the pumps and at least keep her in the list position. In the meantime I got close to a boat and caught on to one of the ropes a sergeant threw me and I climbed up the ladder. No sooner on the deck then I blacked out, probably shock.

The first aid laid me over a barrel and pumped me out. I woke to find Dr. Fogerty poring brandy into me. He said he was twenty minutes in resuscitating me. In the meantime they stripped me of my wet clothes and with just a blanket over me was lowered down into a collapsible boat with others from the ship. There were about fifty of us and many clinging on to the sides those that could swim. The weight of this number kept us going under water to our waists and then like a cork it would rise up. Before I was pulled up the ladder and a distance from the boat “The Ben Macree”, a torpedo destroyer threw a rope to me but I missed each time as the boat could not slacken down lest it strike the torpedo. The Captain sang out, “Hold on for a while longer, a troop ship coming and will drop boats”.

The first aid laid me over a barrel and pumped me out. I woke to find Dr. Fogerty poring brandy into me. He said he was twenty minutes in resuscitating me. In the meantime they stripped me of my wet clothes and with just a blanket over me was lowered down into a collapsible boat with others from the ship. There were about fifty of us and many clinging on to the sides those that could swim. The weight of this number kept us going under water to our waists and then like a cork it would rise up. Before I was pulled up the ladder and a distance from the boat “The Ben Macree”, a torpedo destroyer threw a rope to me but I missed each time as the boat could not slacken down lest it strike the torpedo. The Captain sang out, “Hold on for a while longer, a troop ship coming and will drop boats”.

The troop ship “Scotian” came along dropped boats collecting as many as they could see . Since they also had troops on board they had to drop boats quickly. Like all wooden boats which hung in the weather from davits they were warped and let in water and sank so we had to look for other objects to cling on to, or swim which I could not do at the time. It was not long however, when a hospital ship the “Neuralia” came. I climbed up the gangway naked for I had lost everything. A sister met me at the top and shrouded me with a blanket and I was saved. I was put along the deck with the others and instead of shivering with the exposure and cold, got the condition of rigor which shook my frame and legs violently and this kept going for quite a time. George Quinert, a Ballarat chap, got me some hot soup from the ships galley and then I slowly warmed up .

What a feeling of safety to get out of such an ordeal and to feel safe on a hospital ship. You have to visualise crowded boats, many hanging on alongside only, the heavy seas washing over our heads. Rowing was of no avail as the waves put us back as fast as we moved. The diarrhoea I had when I left Egypt got worse and the conjunctivitis made my eyes sore.

Quite a lot got into difficulties and gave up and were drowned . Some were thrown into the water with the blast and several seamen in the stoke hold were killed. Brigadier Colonel Linton was drowned. We were fortunate in it ‘being daytime and as well there were other boats in the convoy not many hours away on the track. We arrived, the saved ones, at Lemnos-Mudros and transferred to “The Transylvania”, one of the largest ships at that time”.